Jane Myles:

You notice I didn't say decentralized trials space. That's a learning from a site listening session last week, which I had the privilege to lead. Where the sites really said, the more you talk about this as a different kind of trial, the more complicated you're making it. It's really a new set of tools. And it's like, I violently agree and so I'm changing my language. Anyway, welcome to the circle. Thrilled you're joining us. Matt is our circle steward. You have special guests today, and really delighted to welcome you here. Circles are new ish for DTRA, they got started earlier this year. But the benefit of the circle format is that people from any part of any member organization are welcome to join.

There's no title. There's no role. It's just about curiosity and passion. And there's no specific deliverables attached to being part of a circle, unless someone in the circle has this brilliant idea that we need to tackle and then we'll go charter an initiative that will be separate from the circle. So this is a spend your time, get curious and learn who else is thinking about these things forum? Yeah.

Matt Veatch:

Perfect. Thanks. Thanks, Jane. Yeah, super exciting space. And predicated on all the interest in real world data and evidence generation, it made sense to have the circle that would focus on the combination of decentralized research and real world data. Hence the topic today, it's the growing opportunity in the drug development lifecycle. Kind of a fireside chat, and I'm speaking from Colorado where it's getting a little bit colder. The fireside actually sounds pretty good. We'll be talking about where the industry is headed. We've got a distinguished panel. This is so exciting with our moderators Xerxes Sanii, who's the Managing Director of Corporate Strategy and Development at PicnicHealth. And panelists, Kim Barnholt, Executive Director of Evidence Generation at Genentech, Nancy Dreyer, President of Dreyer Strategies, and the former Chief Scientific Officer of IQVIA, as well as Dr. Dan Drozd, Chief Medical Officer for PicnicHealth. So welcome to our guests. Super excited for the discussion today. And I'll open it up initially, just for some very brief additional introductions if you would like. Xerxes, maybe I'll start with you.

Xerxes Sanii:

Sure. I'll start thanks for the intro, Matt. Yeah, Xerxes has been with PicnicHealth for a little over four years. Managing director of the company has spent the last decade or so in various evidence generation capacities in the life sciences space. So appreciate you all inviting us and I look forward to the conversation.

Matt Veatch:

Perfect. Thanks And Kim.

Kim Barnholt:

Great. Hi, everyone. Thank you so much for the opportunity to be here. Kim Barnholt. I am an evidence generation leader in our USMA, our US Medical Affairs group. I've been at Genentech for just over 10 years in various capacities from early stage to late stage and now in the evidence generation part in our medical affairs, which I love because it's actually closer to the patient. It's closer to the real world. And part of what I enjoy in my role now is really bridging across different parts of the drug development lifecycle, as well as bridging across the industry. So looking forward to the discussion today.

Matt Veatch:

Thanks so much. And Nancy, great again to see you and a former colleague and friend. Welcome.

Nancy Dreyer:

So thank you. Hi, everybody. I'm Nancy Dreyer, I'm an epidemiologist. As Matt introduced me I have formerly was the Chief Scientific Officer of Real World Solutions at IQVIA. And I take pride in having introduced Quintiles and IMS Health. But I've been in the business for over 30 years. And I think this is probably the most exciting development I've seen. And the idea of having the voice of the patient together with clinical information and wearables. It's there's not the only bright thing on the horizon at the moment.

Matt Veatch:

Thanks. Thanks, Nancy. Dan?

Dan Drozd:

All right. Thanks, Matt. So I'm really excited to be here. My name is Dan Drozd. As was mentioned, Chief Medical Officer of Picnic Health, had been at the company for about four years. I'm a technologist at heart, also trained as an epidemiologist. And really couldn't agree more with Nancy, that this is a particularly exciting time and I think really an opportunity for all of us to talk, and make real headway in terms of how do we empower patients to really be at the center of what we do clinically, as well as what we do from a research perspective? At the end of the day to improve the quality of life for patients, and to reduce some of that burden on patients for both contributing, engaging in research and also for managing their complex chronic condition. Looking forward to the conversation today.

Matt Veatch:

Great, thanks so much. Great. Again, wonderful panel, and really looking forward to kicking things off. So with that, and directed to you Xerxes, as a sort of moderator for the panel. RWD, what's the focus of PicnicHealth? How does it help advance RWD and RWE in the life sciences?

Xerxes Sanii:

Sorry, yeah. And I think just to keep brief, I think that the tagline that I think we've been using for a while, and nowadays, I think it's maybe becoming overused. But this kind of patient centric evidence generation is where we fall into this space. And I think what that means is, where there are deep data needs, and/or kind of the need to engage with patients, which I think each of the panelists also brought up. So just to kind of orient the group here. When a patient consents, and the infrastructure and technology we've built, enables us to get all of a patient's records. And so that's irrespective of a format where it's living, what EMR system, did they move, are they on the East Coast, the West Coast will ensure they have... And then and then on top of that, also a homegrown solution that's what we call machine guided and human curated, to generate high quality data out of the EMR. And then on top of that, engage with patients directly, allow them to participate and share their voice via surveys, clinically validated PRs or bespoke questionnaires.

And so you can think about, the output of that being almost if you had the time to kind of do a retrospective prospective multi-site chart review later on patient perspectives, and get that volume of data but do it in a very efficient way through the technology we've built. So that's what we've done. A lot of virtual registries that we've built in various diseases over the years, I think to use, Jane, I can't remember Jane's word it was the decentralized space where solutions are. But I think now that we're seeing these novel study designs, incorporating this technology into that direction where we see the industry moving, and they're very excited about the kind of new applications that that opens up for where we go.

Matt Veatch:

Perfect. Well, I think, just in terms of additional stage setting, maybe if you could focus just a little bit and directing this to the panel, some of your observations from the space. And there's obviously been a maturation and use of all types of real world data for evidence generation, and specific to clinical research. And again, broader definition than trials, and not trying to call out specifically decentralized it really is part of just the tools in the toolbox for conducting thorough clinical research of today. And again, spanning beyond trials and observational studies, the classic phase for research. Welcome, your thoughts on sort of where the industry has come from and where it's going.

Kim Barnholt:

Maybe I'll take a quick stab, I think where I'm really excited is that we talk a lot about patient centered trials. And I think decentralized trials or decentralized research is patient centric and that it's really trying to meet patients where there are, it's able to bring tools into their house into their community to allow them to sort of passively share evidence, gather evidence, as well as have more active elements that can be shared remotely. But we've always been, patients are still patients, they're still one element of who they are. And the term that I've heard evolve and start to be used more frequently is human centric trials. So we're taking into account not just the patient as somebody who may have disease, but the person who also has lived before their disease, who may have family and work obligations beyond their disease. And I really see the value of real world data being used in collaboration with clinical data as a way to add more humaneness to the research.

It allows us to have a wearable be out in the world where we're understanding how the person is going about their day to day life, without having it be an artificially contrived setting that we're trying to understand their disease burden or an impact of a drug response. It's allowing us to look at claims data or health record data that may even be before they were diagnosed with the disease and understand some of the progression and the trajectory to that point. So I really see the value and the impact and the opportunity with real world data as helping us be more human centric, and look beyond the patient and look at the more holistic aid end to end of their mind and sorry, and beginning and middle part of their lives and understanding how we can treat somebody to make their whole life better not just try to cure a disease or improve their current disease state.

Matt Veatch:

And Kim, speaking from the platform of a biopharmaceutical company, do you feel that there are specific areas of research that are particularly well benefited through real world data? Or is it across the board?

Kim Barnholt:

I mean, I think it's across the board. And I think we're really starting to understand the opportunities, where we've seen more immediate impact is around rare disease. I think there's an opportunity to start to connect in some of the dots and understand, link in some of the real world data with some of the clinical trial data and maybe fill in some missing evidence gaps. I think it's also in, in terms of some of the wearables and some of those devices, I think it's also where patients may not always be able to travel into the center, to a disease center. And I also think it's with improving access. So really more across the board from some representative and inclusive trials, it's a way we can start to better understand different populations, we can better understand how to provide access and really provide more equity in how we're conducting our research.

Matt Veatch:

Yeah, great thoughts, Kim. Thanks so much. And turning to either Nancy or Dan, we don't have to go in any particular order. But welcome your thoughts around, just observations that you've seen and the applicability of real world data to clinical research at large?

Nancy Dreyer:

Well, because Dan still on mute, I'll jump in. I think we're just scratching the the tip of the iceberg, whatever the right expression is about the missing information we've been blind to. And we always thought, "Well, it's not important." The idea of the decentralized trials, I mean, let's just follow up on Kim's suggestion or mention of the wearables. What you're finding year is not how I do in a six minute walk test after I've traveled hours to get to the clinic, and I'm exhausted and hungry and just... You get really a more accurate measurement of people's movement in natural settings. You also get information from patients that they may not have shared or may not be willing to share with their doc. Now I come out of drug safety, Matt, and that's where I had my roots. And it's really easy to take claims data and blame something on the drug. But when you start to talk to patients, you find out all that valuable information like, "Well, I was prescribed it, I filled it, but I didn't take it because of this or that."

Or, "I took it along with my meditation practice and I really think it's the meditation that made the difference." Or it's the, "I haven't told my doctor about my illicit recreational drugs, which maybe has an effect on my health." So I think you're referring you're giving the opportunity to patients to bring information in a confidential way that could be extremely important to your health, and really have a much more a fuller picture to allow us to evaluate both safety and effectiveness.

Matt Veatch:

Fantastic, thank. Yeah.

Dan Drozd:

I'll just build on that. I really, I think that we see in practice the difference at times between the efficacy of drugs in clinical trials and effectiveness of drugs in the real world. And I think that there are obviously many reasons for that. But the fact that patients at the end of the day are people, right? They're all of us, and you may go to visit your doctor once or twice a year, as Nancy mentioned maybe that's not the best time to do a six minute walk test for you are to check your blood pressure or various things like that. And that our ability to gather that information and really understand what the the overarching journey and experience of a patient as they move through their lives is, is I think incredibly powerful from a research perspective, also incredibly powerful obviously from a clinical and care delivery perspective, which is maybe a whole other topic.

But I think as a physician, anyone who has taken care of patients recognizes that that kind of day to day life challenges that patients have, ended up having significant impacts often on kind of their ability to comply with medications as they're prescribed, the potential effectiveness of those medications in their day to day life and ultimately the impact of those meta medications on improving their quality of life. So I think, lots of possibilities there, both from a research perspective in a care delivery and optimization perspective as well.

Matt Veatch:

Yeah, great thoughts as well. And so just kind of picking up on a thread and something that Jane mentioned in the opening comments is sort of the idea that decentralized is not a separate paradigm. And it is really part of mainstream political research today, and shouldn't be held out as distinct. Does the same hold true for real world data? I mean, should we call out real world data separately? Or is it really part of the ecosystem of how research is conducted today?

Dan Drozd:

Who can challenge that? I mean, it's clear it's become part of the landscape of research today. It's been an interesting journey watching how trust has been built in real world data. Now, anybody who's had access to their medical record might occasionally raise an eyebrow when they see what the doc wrote compared to what they told you. But overall, what you're seeing in medical records is useful. And that's been showing time and time again. So we started with health insurance claims. And we were all frustrated, because it's just a diagnosis code or a rollout code. Now we have the richness of the EMR. So the end, if you look at every real authority around the world, they're all interested in real world data now. I don't think there's anybody who's not open to it and starting to make decisions on it. So we've passed that hurdle.

The question now is, what can you trust that's happening outside the health insurer and outside the supervision of the doc? And my reaction to that is it's about time. Because what we're talking about is tremendously valuable information that we were blind to before because it was just too hard together.

Matt Veatch:

Yeah, great [inaudible 00:17:17]... Kim?

Kim Barnholt:

Oh, go ahead. No, I was going to build on that and say I absolutely think it is part of our ecosystem. And I think we would be stupid to ignore the valuable resource a wealth of information that it provides. I think Nancy said earlier, we're just scratching the tip of the surface of what's possible. And I think the more that we start to integrate it in, the more we'll learn with that. I would say we can't necessarily just consider it all folded in because it is a complex type of data, there's a lot of different considerations around how we work with it, how we structure it, how we are able to harmonize it and integrate it in. So I do think that we're still new in terms of learning how to manage it, and how to understand the quality of it that it takes a little bit of white glove to make sure that we're using it right and integrating it correctly.

So while I think yes, in terms of we shouldn't be shunning it, and we should absolutely be pulling it into the conversations, I think it's not quite at the level of some of the more traditional data sources that we understand really well, that we need to make sure we take some care to bring it in correctly so that we don't go too fast, and then lose the opportunity to actually kind of have it become more status quo, if that makes sense.

Matt Veatch:

True does. Thanks Kim. And Dan, I don't know if you would like to contribute to this particular thread. It seems that PicnicHealth's entire business model is kind of predicated around just the incorporation of real world data. It's central to the corporate strategy.

Dan Drozd:

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I think it's a recognition that we are in this period of transition really between kind of these silos, that have existed in the past. Between what we called real world data, claims originally as Nancy mentioned kind of progression over time. And that what we're at is, I think, this exciting point where we are seeing more and more progress towards towards integration and use of this data across a variety of use cases, kind of throughout the development lifecycle for for pharmaceuticals as well as obviously post approval and kind of more, "traditional" use cases. I think that we're at a really interesting period of time, and as you said this really is core to the way at PicnicHealth that we think about real world data and about ensuring that the patient has a voice in that process.

And that by leveraging kind of the voice of the patient and the access that patients are entitled to to their own healthcare data, that there really is a unique unlock that's possible in terms of collecting more comprehensive and complete data coming out of EMRs. And then being able to link and leverage that data to other data sources as well.

Xerxes Sanii:

If I can add, I think like when Kim was, spilled on a dance that I think when Kim brought up the whole concept of like, human centric designs. As she was saying that in my head I was kind of, that's like practical problem solving for a question you're trying to answer. Right? And kind of to the question of is, real data part of that? I think it is. But I think what's really interesting now, and like what we're seeing a lot and what's I think very promising is, I think people are more willing to have like, are willing to engage in all the nuance that goes into having these decisions. I think a lot of the tension that you see from, I'll just say "traditionalists" and kind of people who are pushing more novel ways or, "This is not controlled," or, "I don't know how to interpret this." But I think as an industry, as a kind of community. I think having those nuanced discussions that again, Kim was alluding to, "Hey, this data is actually useful for this, or this wearable will solve this problem."

I think we're all kind of at a place where we're willing to really think about these things in more individualized ways. And I do feel like that has been a big driver of some of the progress that we've seen recently.

Matt Veatch:

Yeah, fantastic. And Xerxes, just out of curiosity, because of your role and really managing corporate strategy for the company. One of the things that I was kind of reflecting on is the some of the negativity in the press around accessing data. It's almost always, for the lay person, the lay consumer, the lay patient out there in public, it's always presented in kind of a negative light. There's data access breaches and things like that, how is it that... And what are some of the ways that that's mitigated? Where patients are made comfortable to share their data, to grant consent, to allow that access to their records?

Xerxes Sanii:

Yeah, it's a great question. And I do think that to some degree, there's no generalization, I think, still remains in. But I think there is sometimes a misconception that people don't want to share their data. I think, especially when you're going through something... We see people all the time, "I'm going to go do a walk for this disease." Or, "I want to do like..." I think wanting to make meaning I've been wanting to contribute in a certain way. And so I do think there is, in many individuals like an inherent nature to want to contribute. And I think those challenges you alluded to are certainly there of, "Hey, what about data breaches, or who will see my data?" And so I think our philosophy from the beginning has always been consent and transparency. Everyone on this call is in the aggregated claims data set, right? And it's going left and right. And so I think our model has always been own your data, be empowered with how it's used, who it's shared with.

And I think just a core principle of a company from our founder, that I believe will never change is just kind of giving patients that ability to turn that switch off if they want. And then just being able to explain... People don't want to hear about cybersecurity details. Right? But I think just being able to communicate in clear, layman's terms, how data is kept safe, and what certifications you may have things like that. So, I think trust within the patient populations that we serve is paramount, for sure in everything we do.

Matt Veatch:

Absolutely, yeah. And just the stark differences between the randomized control trial, which is informed consent is a critical component of that, versus real world research which is obviously can be consented, should be consented, depending on the the nature of the research. But those worlds in some ways have kind of collided. And it's interesting to look at the impact and how that affects patient engagement, specifically. Any other thoughts about, from the patient perspective, sort of signing up for something where their data is going to be accessed. Any sort of real world examples of where that's worked particularly well in a research project?

Nancy Dreyer:

I can offer pandemics. I mean the big push in the pandemic is when decisions can't wait, you have to do something. And we often saw patient centered, patient driven research come to the forefront is critically important. Kim?

Kim Barnholt:

Yeah, I was actually going to speak with a little bit of a previous role have that I used to work at 23andMe and with digital patient communities, and a lot of it was sharing genetic data in the spirit of research and moving the needle forward in terms of discovery. And we found or I guess, I personally found in working with patients, they were actually some of the most likely to share. I think they there was a real need to get answers and they were very driven to be part of that process, and it almost was empowering to be put in a position where they had some data to contribute towards something that was helping them, but also helping the community of people that that were having similar experiences. And I think there's almost, and again, I think you can't generalize and not everyone is the same.

But sometimes by making this part of something bigger, a part of a process, there is something very empowering about consenting to share and being part of research versus, as you said, kind of claims data on EHR data that may be passed around anonymously that you don't have any say in or control in. And so I do feel like when people feel like they're a partner, and they feel like they're empowered, and it's a decision, and they're doing something that is active and proactive, that people are more likely to share, and it almost builds more trust, because there's transparency to it. Versus sort of what you don't know, and you make assumptions and layer a narrative on around that.

Xerxes Sanii:

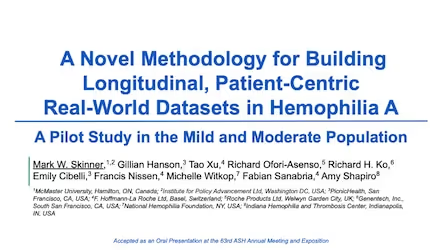

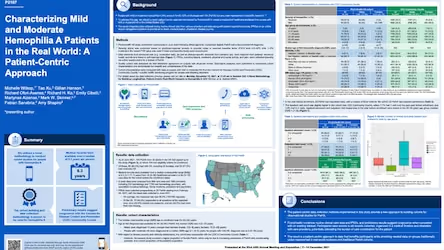

Kim, I think you just triggered one thought which when we worked... One thing I've come to realize more than I think I appreciate it before is oftentimes the way kind of patients see their disease, clinicians see it and researchers see it can can also be so different. And one, we've done some work in hemophilia recently. And as part of that did a lot of surveys that were geared around, do you feel anxious around when you have to infuse yourself? Or what are like, some of the things that people don't often talk about of like there's a whole treatment journey. And oftentimes researchers they see it as, how often are you bleeding in a six month period, a 12-month period? And the participation and just like the unsolicited messages we got from patients. "Oh, thank you for asking me about this." And they were really eager to share about their experiences with these things.

But it's something that they had just never been asked in either a research or clinical setting, but was very top of mind for them in terms of how their disease impacts them and how they feel day to day. So that was a pretty eye opening experience for me.

Dan Drozd:

This is building off that a little bit. I completely agree. I think that the kind of empowering patients is clearly a very different kind of model than many of the things that we read about in terms of data breaches. "My data was stolen from Home Depot, because I bought a hammer there." or something like that, right? This is very, very different. And so I think that giving people choice and giving people the power to proactively consent into a data set rather than being included without necessarily their knowledge, or in some little addendum at the bottom of a forum that they happen to have signed when they went see the doctor is very empowering to people. And as Xerxes said that kind of asking questions that aren't necessarily the sorts of questions that might have routinely been asked in a clinical trial, for example, and really understanding a much more complete and 360 degree view of a patient's experience and how their illness impacts their life.

Not necessary, which may be kind of a hard clinical outcome that we might look at in a trial, or it may be something completely different as Xerxes said, anxiety around time I need to infuse factor in hemophilia patients. And the other thing that I think we've danced around maybe a little bit is value to patients, right? And value can come in kind of many different ways. And certainly one value can be fulfillment of this. How do I make meaning out of my own journey with this condition or with this disease? And is there a way particularly for conditions that have some genetic predisposition? If you're diagnosed with something and you know that your child has the chance to develop whatever that might be, this becomes an incredibly powerful motivator for people to contribute, obviously. I think that our platform in particular really kind of places an emphasis on how do we ensure there's a voice for a patient? And how are we making sure that as researchers, we're thinking about the patient as more than a series of numbers or kind of traditional outcomes?

How do we provide value to patients in terms of in many cases, providing a platform or a vehicle for people to be developing some meaning from their own journey and what they've been through. And then lastly, very tactically, like just having your records makes your life easier, right? Like people change doctors and health care facilities all the time. All the time you changed insurance because you got a new job. And I think for patients with complex conditions, there's a project management kind of components of what they... We all have that in many different places within our lives, but the extent to which we can take some of that burden off the patients and really allow them to live more fulfilling and meaningful lives and have less of their time consumed with kind of managing the busy work of their condition, I think is a real value adds for patients and ends up being extremely powerful the motivator as well.

Matt Veatch:

I love that. It's the voice of patient. It's empowering the patient as part of the research process. It is part of decentralized. It's bringing the research, the modalities, the tools to them in a way that really changes the research paradigm overall. I think it's great. And that kind of leads to another question in my mind. It's one thing to have patients understand the value of their real world data and consenting for that. It's another to actually have them participate in a trial or a study. What's necessary to sort of bring the patient from that agreement around their real world data to actually participating in a study? Dan, you have any thoughts about that?

Dan Drozd:

Yeah, I think the answer is it depends, right? It depends on the objective of the study, it depends on what's being asked for a patient in a particular setting. But I think the more that we can move, reduce barriers towards patients participating in trials. So we've talked some about wearables and other kind of, we can talk about patient reported outcomes and other ways. In the Haemophilia cohort that Xerxes mentioned, while we do gather a lot of information around things like symptoms that patients may be having, or as he said, kind of anxiety in the context of infusing factor. We also ask patients about kind of much more traditional measures, how often are you having bleeding events, etc. And so I think the more that we can simplify and make kind of lower burden for patients, reduce the number of times that patients need to go in to travel long distances, to go into sites, if we can do phlebotomy at home, all of these kinds of things. There's collections of tools that we have in our toolkit, and the right combination of those tools obviously depends on a particular study.

But I think unquestionably the more that we can lower barriers to patients participating, the more, the easier it is to get patients to participate. And I think at the end of the day, the richer the data that we'll be able to collect.

Jane Myles:

And I'm going to double click there. I have two questions, but I'm going to stick to one for now. So when you give patients their medical record, are they also asked if they are willing to be contacted about clinical trial opportunities? How does that work? Because the last mile is just such a big hurdle right now?

Dan Drozd:

Yep. So we do have the ability to do that. And whether we do that depends entirely on specific situations. Right? So we do have the ability, we obviously... Part of what I think at the end of the day PicnicHealth's biggest value proposition is, is that contact and ability to work. That relationship that we have with patients directly. Right? And so there are a lot of things that that unlocks, potentially from a clinical care perspective, from a research perspective, etc. And I think that, yeah, so the simple answer to your question is that is the sort of thing that we have the ability to do, and whether we choose to do it in particular conditions, or that varies depending on the situations.

Jane Myles:

I would say don't undervalue that. There's tons of de-identified data sources which are helpful. But the direct contact to an identified patient with their consent is golden.

Dan Drozd:

I could not agree more that if you asked me to pick like what is our biggest differentiator it is as an organization amongst many other things that we've alluded to here, I think it is that relationship with patients, that direct relationship with patients.

Matt Veatch:

That's great. I think Kerri had a question. Oh, sorry, someone...

Nancy Dreyer:

That was me Matt, I was going to just amplify what Dan said about being human centric, to use Kim's word because it's great. Because that relationship, that connection and Jane your point about a faster way to recruit and get right to people is huge. But then that ability to... The thing I think that's cool about what Picnic is done is they're already doing something of value for the patient regardless of research. So we start out giving patients something they can benefit from day in day out, period. Now when you add things on that you've already got an enthusiastic user base. I think that's got to be important.

Kim Barnholt:

And building on that, Nancy, I think some of the hurdles to trial awareness, trust and access. And I think that the more that patients start engaging with their data in the real world, so a lot of people have an Apple watch or a Fitbit, they start to get more comfortable with data, they start to understand what they're seeing in their own life whether they're a patient or not a patient, you can start to see trends, you can start to, "I don't feel well today. Wow, I didn't sleep well." Also, we're starting to introduce... And then Picnic is a great company around introducing access to medical records, taking away that stigma that that's something a doctor take notes, and then you never see. So we're starting to onboard... Sorry, my phone is going. We're starting to familiarize people with data with kind of the what data means, how data translates into opportunities for improving your health or to be empowered around decision making as part of your health or part of research.

It removes raises that awareness, it removes some of the barriers that might start building the trust, because then you're shifting the conversation. And then I think with some of the decentralized approaches through real world data, but then also some of the decentralized trial elements, we're increasing that access. So you're starting to touch on each of those barriers that I do think real world data plays a critical role in helping us address and remove for broader participation.

Matt Veatch:

Great points. Thank you. Kerri, I know you had a question. And if not to put you on the spot. But we would welcome your question and maybe it's already been addressed.

Kerri Cali:

Hey, Matt, yes, of course, thanks so much. And I apologize, I was a little bit late, I'm just coming off of... I'm still on parental leave for two more weeks. So my baby's awake and alert right now. So I'm going to stay on mute as much as possible. But, two things. One, I wanted to build on something that Jane had said, and then something someone else said earlier. But what I find really interesting in using real world evidence is twofold. It's one using it to find patients for trials, and then to how we incorporate the data in the trials. And to build on what Jane said, it's like using it as clinical research as a care option. So having that as an option. So when a doctor tells the patient, "Hey, these are your options for treatment, including clinical trials." I worked a lot in multiple sclerosis, cancer, other neurology studies. And that's what the doctors, a lot of them who are trained in research, they just tend to do that. They say, "Here's what's available in terms of treatment in terms of clinical trials."

It would be better if more folks were educated about that so they could do that. And also, on the other end of finding patients, which leads into clinical research as a care option. One thing that we're looking at in some oncology trials is using some of these genetic testing vendors to find patients. However, for those mutations that are not treatable mutations, a doctor might not necessarily look for that. And it might be difficult to to find in an EMR record. So we are using some genetic testing vendors to find those patients and offer those trials to them as a care option. But a few and far between and it's still kind of newer, a newer thing that folks are doing. So we're testing it out seeing if it's going to work. And I didn't introduce myself from before. So I apologize. My name is Kerri Cali and I currently work on the sponsor side of things. I'm at recursion out in the Midwest. And we're a tech bio company working in rare disease and oncology right now. So I'll just pause there and see if anyone has any thoughts or comments on that.

Matt Veatch:

Great points, Kerri, and I think it is such a critical, I mean, taking your second points around the incorporation of genomic data and looking for various biomarkers. I think increasingly, that's becoming central to research, certainly talking to a lot of sponsors myself, understanding what they're looking for, and where their research is migrating towards, there are considerations. And anytime you're capturing genomic data and returning results to patients, there's an obligation to provide genetic counseling, for example, and how that's managed, those are really designed considerations, I think, for the nature of the research.

And Kim, turning to you not to put you on the spot, but given your background and former roles, is that something that you are actively thinking about in the new role. It's how genomic data can influence the design or conceptualization of a study, because fundamentally, we're talking about decentralized again, it's just another tool in the toolbox. So really the core issue, why is the research being done in the first place?

Kim Barnholt:

Yeah, I mean, and I'm a little bit far from the the genetic side of things now, but I do know there's a Genentech in many companies personalized healthcare is the Holy Grail. It's 10 week. Ideally best target the right drug, the right patient at the right time. And biomarkers are absolutely a key to that. So it is a core part of a lot of the design of our trials, particularly in the oncology space. I think where real world data can add value is thinking about patient burden, if they're already having lab tests, if they're already doing some biomarker testing, rather than making them go through biopsies again, and again, potentially, can we pipe those data and use that as part of their screening? Can we better understand, is this patient the right fit for this trial, rather than making them go through multiple test, drive hours to a new center. Even from a sponsor side screening can be very expensive or rolling up a site can be very expensive. So is there something we can know about the patient's fit for the trial, to optimize the patient's experience, to reduce screen fails, it's expensive to sponsors, it's frustrating to patients.

And I think leveraging the data, the genomic data that we already may have, through the course of a patient's treatment, would reduce frustrations, costs, and just barriers all around as well as ideally, setting the trial up for success, which then is more in the space of, more likely to get the drug out to the market for the right patients who it may work for. So I am a strong believer in that. I also believe, I think one of the things, Kerri, to your point about in the perfect world, we have physicians to understand about their patient, whether it be biomarker driven or certain disease characteristics, and recommend either the care option or a trial as a care option. I'm not sure we're quite there yet. I think that's something that we really should strive towards. And I think where we're seeing, maybe the greatest opportunity to continue through this education awareness is in some of the underserved populations where they aren't necessarily always given the trial option.

And so I think that's something also that we're working with, within our company is how can we better connect in with community sites? How can we provide them with data potentially, they may not already have about their patients that would help them better understand a fit for trial, as well as helping make sure we're aware of trials to be able to refer those options for their patients.

Matt Veatch:

You can just build on that for a moment and finding those underrepresented patients. There's a lot of talk and discussion. And in fact, an entire forum discussions around social determinants of health, is that something that is often from the medical record, it may or may not be as comprehensive as needed to really make those determinations. Is that something that you think about in terms of how to sort of enrich the existing and accessible data with social determinants?

Kim Barnholt:

Absolutely, I think it's a really valuable data source. I think it's still finding the right quality of social determinants and kind of the right data source, having that information. But one thing that we're really excited about is data linkage. It's having trial data but then it's layering on real world data sources to help enrich the information that we're gathering through the trial process. And social determinants is absolutely a critical data source for being able to better understand the influences of different societal factors on to a patient's health and health outcomes.

Matt Veatch:

Yeah, fantastic. So we've got about 15 minutes left, and I just want to encourage additional audience questions and sort of take advantage of some live participation. And while we're waiting for hand raises, I will turn to another question. And that's the the conundrum of working with real world data. It's powerful in many ways. It's also notorious for its data missingness. And trying to overcome that missingness is something that is critical to its uses. It sounds like PicnicHealth would be in an ideal position to bridge that because you can just ask the patient questions or get additional information. And I'm curious to see to the extent that PicnicHealth actually tries to enrich the data that's coming in. Could you touch on that just a little bit?

Dan Drozd:

Yeah, happy to. So yeah, we do think that this is a really unique position, that we're in a really unique position to address this issue. And so we think of missingness in a couple of different ways. So if you look at a traditional EHR data vendor for example, they may have data only from a subset of sites that a patient may have been seen about, is seen at. So you may be missing clinical outcomes, key predictors, a biopsy report, a result of imaging etc. And so because at the end of the day, the patient really is the only through line and their journey through the US healthcare system. We do think that by putting the patient at the center of that process that unlocks the ability for us to go out and collect more comprehensive and complete records for patients, we have an entire both technology and kind of operational components of the way that we think about trying to meet that challenge. So that's kind of one component of completeness, there's both a lot, there's a longitudinal component to it. And there is also a data depth and missingness component to it.

And then the other part that you alluded to, or the kind of the other way that we think about it, as you said is how can we enrich that data, things that may not be present in any EHR record? So we've talked about, okay, if there's a biomarker that isn't routinely tested, because it's for an untreatable mutation, that that may not be something that a doctor or physician is going to order for a patient. So there, we do have, depending on what the kind of key missingness is different mechanisms where we can link to other data sources, that direct relationship with patients obviously enables us in situations where it's as "simple as asking," we can go and ask the patient about particular data, administer ePRO or something like that to the patient, if that's the kind of core data that's missing. But I think lots of ways that by putting the patient at the center of that process that you really kind of unlock the ability to help address that missingness challenge.

Matt Veatch:

Great. Thanks Dan. Turning to Jane.

Jane Myles:

Yeah, I warned you ahead two questions. I have an infinite list. But this one is about what you were just talking about, Dan. So real life. I've lived in the same house for 22 years. But it turns out, there's nothing in my EMR before 2012. Nothing. I've had the same practitioner. But if you were trying to screen me for a trial, you wouldn't know anything about my diagnosis. So how do you solve for that gap? Like the data is there, but it's not in an EMR?

Dan Drozd:

Yeah, so our... The answer to that question is, at the end of the day, we can only collect from a record perspective what's there. So as long as it's there, right, and that's a big caveat in some situations, right? If you're a practitioner, your practitioner isn't required to hold on to your records in perpetuity, right. So there's expiration of requirements for maintenance of records. Obviously, the those laws largely come from a period of time in which physicians had paper charts, and we're having to pay to store things in warehouses. But so for older records, we do have the ability to get them as long as they're there. And the way that we approach our kind of data ingestion pipeline is at the end of the day, will collect records in whatever format they happen to come in. Any clinicians on the call certainly know that the fax machine is still five bar, the technological implementer of choice for data exchange, from physician to physician.

When I talk about this to non physicians, that boggles the mind, but there's no question that if you're at a doctor's office, and they want to get records from another doctor's office, they are going to call up that office and give them their fax number, and those pieces of paper will come rolling off the printer. But our data ingestion system is really built to ingest data no matter how it comes in. So we have records. To be clear, I'm not saying this is the norm. But we have records for patients dating back to the 1950s handwritten records dating back to the 1950s. And so we're able to leverage technology in our in our core platform, to take those records, run them through a data processing pipeline, generate text out of those records, and then structure that data.

And so at the end of the day we're able to harmonize that data that's ingested. And we should be mindful of the challenges there and limitations of that, of course. But core pieces of data, we're certainly able to abstract from paper records, faxes that come in, we're obviously very happy and increasingly seeing electronic access to data. But I think most people on this call probably know we're not really there yet.

Matt Veatch:

Great. Yeah. Thanks, Dan. Now Kerri, I think you may have had another question, not to put you on the spot again, but welcome your question.

Kerri Cali:

Yeah, it was just one building on something and I apologize asked this question earlier, a few minutes that I wasn't on. But I was thinking more about how you incorporated that real world data and clinical trials. There's so much burden on the site and the patient in especially in oncology trials for duplicative pieces of data. So I'm curious about how you utilize those records. And I recognize that it's probably an early stages, and a lot of folks are working to do this. But just curious of what you've seen so far in your experience, and how you can be more efficient using real world data to minimize the burden on sites and patients and duplicative data and errors as well.

Dan Drozd:

Yeah, I'm happy to offer kind of the PicnicHealth version of that, but I think it'd be good to hear from Nancy or Kim as well. So we do a significant amount of work in this area and multiple mechanisms, we're kind of integrating that data into existing clinical trial infrastructure, depending on what the specific use case happens to be, is the data being used for screening, is the data being fed into an EDC directly or indirectly, in some way, etc. And so is a real challenge for sure. And we definitely appreciate the fact that if we look at like what the substantial challenges are, obviously a number of challenges today, but site burden is clearly a large challenge and making sure that we're minimizing burden on sites and ultimately, hopefully, allowing more and a broader kind of diversity of sites to be able to contribute to research is certainly top of mind for us as well.

Kim Barnholt:

Yeah, leveraging the EHR, maybe reducing double data entry from sites so they can use just directly, have the EHR be fed into the EDC. I think wearables is one way, maybe we can do some of the remote collection at home. So it's not necessarily having to go in and have an assessment being done out of sight but something that patient just directly is gathering. We're also looking at real world data in some of our long term follow up studies. So are there ways that we can and this is sort of where we're applying data linkage. Are there some things that we can do if a patient who is willing to consent to be tokenized, or some other way where we can anonymously connect their trial data to their real world data, do a the latter end of a trial, through real world data follow up versus having it be part of a traditional trial setup.

So these are the some of the areas where we're looking at real world data, and implementing and trials. Obviously, we're leveraging it for helping with trial design helping us better understand inclusion exclusion criteria, helping us find patients and sites. But within the trial itself, and from the evidence perspective, it's I think that the biggest potential we're exploring right now that we see the most obvious immediate value is some of the longer term follow up areas. And also talking about missingness trials that may have some optional assessments where patients aren't completing all of the assessments, can we fill in some of those gaps with real world data, and so that we are more powered to get the insights that we're trying to derive through the trial itself?

Kerri Cali:

Thank you Kim and Dan. And one more question on that. And if you want me to be a little bit more specific, as well, so I'm thinking about scans, right? Sometimes in a trial, they'll say, "Okay, well, if you've had of scan in the last six months, that can be included. And then you have to have at your baseline visitors sometime in screening two weeks prior to the baseline. So I'm just curious in terms of scans, given that you have all these other vendors that maybe are on a study to perform the assessment, so then you have to get the scan in some format that works for them. So then that's it, this becomes a burden for the sponsor, for the participant, for the site. So I'm curious, how will it work for scans? Or how are you guys seeing it work for scans? Is it easier? Is it getting better?

Dan Drozd:

Yeah, so we do actually collect raw DICOM images from CT scans, MRIs, plain film, X rays, etc, and have access to those, both give you access to those patients directly so that patients can look at that data through a viewer within our application, but also then have the ability to share that data in that kind of industry standard DICOM format, which can be loaded onto a fax machine etc, for radiologists to read. So can share both with patients and then with sites potentially, both ORION and Jiang and to the extent that it's relevant for a particular process, the report that was generated by the reading, the original leading radiologists as well.

Matt Veatch:

And then just to pick up on one thread there, and that could have triggered in my mind the thought that often in research there's Core Labs involved with imaging. I presume PicnicHealth works with a variety of partners. At least looking at domain experts, is that something that is possible for the company to do?

Dan Drozd:

Can you...? I'm not sure I totally understand the question.

Matt Veatch:

Yeah. Say at Core Lab was involved in looking at images in a trial, is that a partnership that you would engage in depending on what the sponsor wanted to do?

Dan Drozd:

Yeah, absolutely. We have kind of a broad suite of partners that we've used and are certainly open to exploring kind of relationships with other partners as well for specific use cases. So, absolutely.

Matt Veatch:

Great. It pains me that the hour just kind of whipped by it's been a great discussion, I'd like to turn to all of the panel and Xerxes as well, to just kind of give final thoughts. Xerxes, maybe I'll start with you. The question being given your role and rebidding strategy, what comes next? I'm presumptive, it's US focused for now. Is there some international expansion for the company? What are some of your thoughts around your corporate strategy?

Xerxes Sanii:

Yeah, I mean, I think a lot of this conversation kind of alluded to it. There's a lot of kind of small incremental changes we've been making and how kind of research is done. And I think just continue to keep our head down that path. I keep going back now to Kim's kind of human centric, and what's the practical way in which we can create trials, I think there's advancements in technology that we've contributed to, in some part. But there's just the human centricity that we are able to design trials with is increasing, thanks to those advancements. And so just continuing to kind of move along that spectrum and just making these designs more possible, by ensuring that the scientific rigor and all the other kind of components of the study, still meet the overall goal. So I think continuing down the path of long term follow up came up a lot in the end of this conversation.

And I think that is one area where we see a lot of opportunity where you can imagine the future of every clinical trial there's almost like, a checkbox or when you're designing it and when pharma companies are designing their trials, "Hey, do you want to link to these datasets? Do you want to generate patient mediated Picnic like data." Then it becomes kind of more than norm. I think that that is kind of a big part of the future that we're looking to shape.

Matt Veatch:

Great. Well, that's fantastic. And, Nancy, in sort of closing commentary, I'm sure you're asked this a lot, given your vast experience in designing research. When is it appropriate to focus on the real world data, you start with a research design? Is that something that you consider the real world data source upfront? Is it sort of as you're conceptualizing the protocol? When does it become the factor that you incorporate into the design itself?

Nancy Dreyer:

Well, studies, I found, are always better when you start with real world data. Because if anyone on this call, who does clinical trials knows how challenging it is to enroll, and part of the enrollment challenges are often due to having nice to have, Ron generously called them inclusion/exclusion criteria, there may be somebody suggested sitting around the table thought it was a brilliant idea, they didn't know would knock out 90% of their eligible population. So we use real world data a lot to see if the patients exist. So I think that's important. But Matt, I can't leave, one of your comments about missing data. I mean, I think the myth was that all data that's not there is missing, because you didn't report it. Not that the test wasn't done. And when we have the EMR and when you can do source data verification by checking back with the EMR, I think that will reshape a lot of people's ideas of what you should have done, but you didn't for whatever reason, we're not missing it, it wasn't done. Thank you.

Matt Veatch:

Yeah, great, great points. Thanks, Nancy. Kim, turning to you, from the sponsor perspective. Just thoughts on the future and sort of your role and use of real world data. You've touched on many topics today. Any kind of closing comments?

Kim Barnholt:

No, I mean, I think we're working internally, as well as externally to really help shape the ecosystem where real world data does become more part of practice. And I think, taking a very practical approach to finding the use cases where it makes sense to continue the conversation. We started where I think in the past, historically real world data, and then your randomized clinical trials were very far apart and we're moving towards where these are now part of the same conversation and really working as a cohesive set of evidence to be able to understand the patient experience, understand disease and really understand drug response. And I think we're on that journey. I'm excited to be part of that journey. And I think, as a data geek at heart, we have so much data in the world, I think we could answer so many questions if we just start connecting it, mining it, reusing it. And I think real world data is just a key part of that treasure trove that we should not ignore.

Matt Veatch:

Love it. Great, great comments, great thoughts. Dan, turning to you, Chief Medical Officer at PicnicHealth, what are you most excited about in terms of the incorporation of data into clinical research at large?

Dan Drozd:

I think it's really at the end of the day, just increasing access and the ability of patients to contribute and making sure that that voice of the patient is really at the center of the research process. That when we're generating evidence that it's being generated with the patient and the impact that that our treatments can have on how they live their regular lives, not how they live their lives when they walk into physician's offices intermittently.

Matt Veatch:

Fantastic . I know unfortunately, we're out of time, but this has been fantastic. Special thanks to everyone, participants as well. And we look forward to the next circle discussion coming up, to be determined. Maybe our date has been set, I think it has. But I'm really looking forward to that. Closing comments from Jane and Paige from an administrative perspective.